A CLASH over India’s drug market was inevitable. Foreign drugmakers, facing paltry growth in the West, are eyeing India hungrily. Rising incomes and rates of chronic disease may push sales from $12 billion in 2010 to $74 billion in 2020, according to PwC, a consultancy. But tapping this growth means having patents that protect intellectual property. India is home to a thriving generics industry, whose copycat drugs make up about 90% of the market. India’s drug-patent laws are just seven years old. Its government is keen to encourage generics and keep prices down.

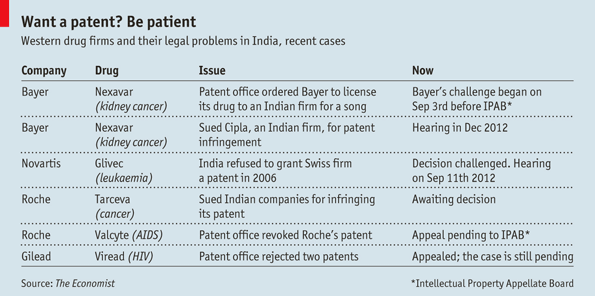

Now India’s patent rules are being put to the test. Novartis, a Swiss giant, is challenging India for denying a patent for Glivec, its blockbuster cancer drug. The fight is due to reach India’s Supreme Court on September 11th. Bayer, a German drugmaker, has a different problem: in March India’s patent controller ordered it to license a drug to a local manufacturer. Its appeal had its first hearing on September 3rd. The cases will help decide how quickly India’s 1.2 billion people get new drugs, and at what price.

India’s drug industry has a unique history. For more than 30 years, the country did not recognise pharmaceutical patents. Domestic firms became masters at copying medicine and making it cheaply. After joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, India had to change its patent policy. But its new system, in place since 2005, includes special protections for both patients and generic manufacturers.

For example, the law bars patents of minor changes to existing drugs, a practice known as “evergreening”. Drug reformulations are often used to extend patents elsewhere; they get no protection in India. The country also has broad criteria for “compulsory licensing”. A WTO agreement allows countries, in some instances, to force a firm to license a patented drug to a generic company. India’s rules give officials broad powers to do this.

Now both provisions are under attack. In 2006 India denied Novartis a patent for Glivec, calling it an unpatentable modification of an existing substance, imatinib. Novartis insists this is nonsense. Only by making it in salt form, imatinib mesylate, did Novartis have a proper drug: the body absorbed the medicine 30% more easily.

Paul Herrling, the chair of Novartis’s Institute for Tropical Diseases, says the case is a test of what is patentable in India. “We are being accused of evergreening,” he says. “Having that concept applied to Glivec, which was one of the major breakthroughs in cancer therapies, is completely ridiculous.” Michelle Childs of Médecins Sans Frontières, a non-profit, retorts that drug firms such as Novartis should not win patents for minor improvements. This would keep generics off the market, driving up prices.

Bayer’s case is equally heated. In 2008 it won an Indian patent for Nexavar, a kidney-cancer drug. But in March India’s patent controller issued the country’s first compulsory licence. He wrote that Bayer had not made Nexavar “reasonably affordable” (Bayer offered it for a whopping $5,000 a month), that the company failed to provide enough of the drug and, in a protectionist nod, reckoned that importing Nexavar further hurt Bayer’s case. The controller ordered an Indian company, Natco, to sell Nexavar for one-thirtieth of Bayer’s price. Bayer will receive a 6% royalty. Meanwhile Bayer is fending off another competitor, Cipla, which has sold generic Nexavar in India for years.

As these cases drag on, India’s government is considering other ways to get cheaper medicine. It plans to offer free generics in public hospitals, which would drive up sales of very cheap copies. It may also set price controls for patented drugs. However, generic companies are not immune to regulatory pressure. Ministers plan to expand price controls for a broader swathe of generics.

“We realise the industry will take a hit,” explains D.G. Shah of the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, which represents big generic companies. “We’re trying to find a solution so that the government’s concerns on access and affordability are addressed without threatening the long-term growth of the pharmaceutical industry.” Nice work, if they can get it.