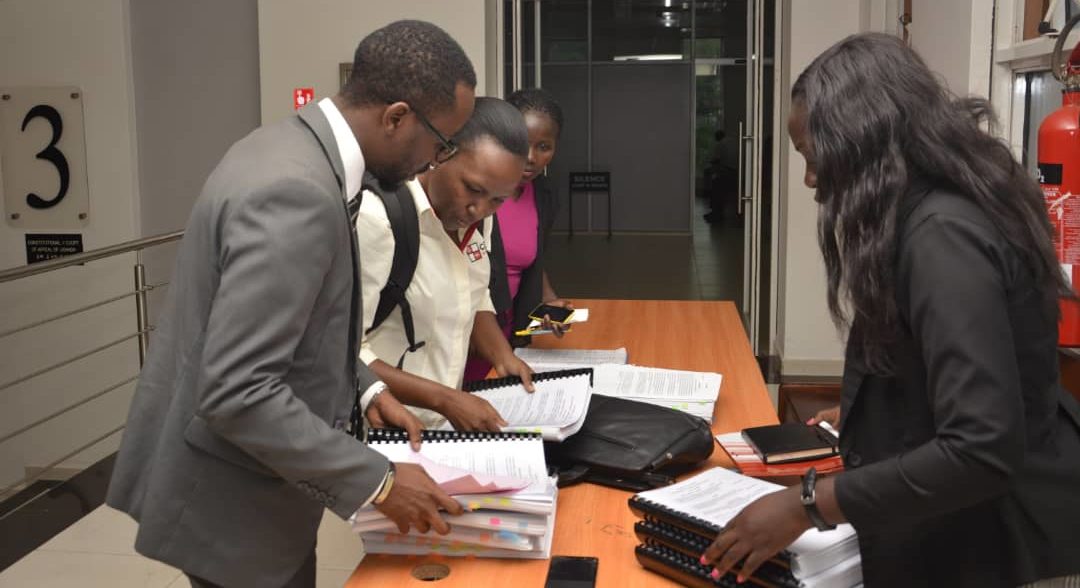

The Constitutional Court of Uganda on 30th September, 2019 formally heard Constitution Petition No. 16 of 2011. This case was filed in 2011 by the Center for Health Human Rights & Development & others against the Attorney General, challenging the unavailability of basic maternal commodities, the unethical conduct of health workers in public health facilities and failure of government to provide emergency obstetric care services among others.

On 2nd October, 2018, the President of the Republic of Uganda, His Excellency, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni officially commissioned the Mulago Specialised Women’s and Neonatal Hospital which was constructed to offer specialised services to women and children. On 18th September, 2018, Dr. Ruth Acheng, the Minister for Health made a ministerial statement on the operationalization of Mulago Specialised Women’s and Neonatal Hospital wherein she stated that there will be user fees charged for the services offered at the Hospital. The pay policy put in place categorised services offered at the hospital as Standard, VIP and VVIP services. Furthermore, a waiver committee to determine who qualifies to access free services at the facility was to be put in place. This is an act of retrogression in the progressive realisation of the right to health and access to medical services. This prompted the Center for Health, Human Rights & Development to file Miscellaneous Cause No. 235 of 2019 against the Attorney General challenging inter alia the act of turning a public service into a private hospital at the Mulago Specialised Women’s and Neonatal Hospital.

It is over eight years since Constitutional petition No. 16 of 2011 was filed but there has been no redress from Court. Maternal deaths continue to happen in both public and private health facilities; some of these deaths are reported, others are concealed especially those happening in private health facilities.

In private health facilities, the vice is on rise leading to high maternal deaths; there are several instances of maternal deaths due to negligence and we highlight a few in this article. On 28th September, 2018, a mother admitted at St. Charles Lwanga Hospital in Buikwe District died along with her baby because of the hospital administration’s failure to refer her to another hospital for better management. The medical personnel supposed to attend to her were not on duty and the cashier tasked to provide the medical bill for payment before the discharge and referral of the mother was absent.

On 13th March, 2019, a mother lost her child at Alshafa Modern Hospital in Jinja District because the doctor supposed to attend to her reached the hospital late and the insistent requests by her to be referred to another facility were rejected. On 12th July, 2019, another maternal death occurred following the actions of a doctor at Butiru Chrisco Hospital in Manafwa District who failed to refer an expectant mother for better management because that referral would cause his hospital to lose funds which were being paid by USAID under the Uganda Voucher Plus Activity. On 20th October, 2018, a mother admitted to Kibuli Hospital underwent a cesarean section and spent over four hours in the theater; she was wheeled out of theater and placed in the ward while still unconscious. She was unattended to for more than 6 hours despite the fact that she was bleeding and eventually died.

These continuous maternal deaths raise the big question on who bears responsibility for all these deaths. Under Objective XX of the National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy of the Constitution of Uganda provides that the state shall take all practical measures to ensure the provision of basic medical services to the population.

The right to life is guaranteed under Article 22(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda. Clause 4 of the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council Code of professional ethics states that a practitioner shall not violate the human rights of a patient, the patient’s family or his or her caregiver. Furthermore, a practitioner is not to carry out any specific actions that constitute a violation of bill of rights enshrined in the Constitution of Uganda and international human rights law. Are health workers really aware about the provisions in the bill of rights or other international human rights laws in respect to health?

In Uganda, the health profession has many bodies that regulate the different medical professions; the Medical and Dental Practitioners Council is a body corporate established by an Act of Parliament – the Medical and Dental Practitioners Act, Cap 272 responsible for licensing, monitoring and regulating the practice of medicine and dentistry in Uganda. The Nurses and Midwives Council established by the Nurses and Midwives Act, Cap 274 mandated to train, register, enroll and discipline nurses and midwives of all categories in Uganda. The Allied Health Professionals Council is established under the Allied Health Professionals Act, Cap 268 mandated to regulate, supervise and control allied health professionals (Clinical officers). When a violation of human rights in respect to health particularly through medical negligence arises, complaints ought to be lodged with the appropriate bodies.

How then do these bodies that regulate the health profession and other stakeholders contribute to the reduction in maternal deaths in Uganda? The Uganda Law Society has partnered with the Uganda Medical Association in a number of activities for example on 30th August, 2019, the Uganda Law Society organized the first ever Health Awareness Day for lawyers and invited the President of the Uganda Medical Association who came along with a team of doctors to speak to the lawyers that had gathered. This partnership is a strong partnership and an avenue for lawyers, medical professionals and other stakeholders to learn and embrace a human rights-based approach to tackling issues that arise in respect to the right to health.

The Ministry of Health is a key stakeholder in respect to health-related matters since it bridges the gap between the people and the medical profession since it supervises both government and private health facilities within the country. Many public health facilities in the country have no medicines, basic services, no trained health workers to attend to people seeking health services including women seeking maternity services. In the absence of immediate intervention by medical professionals, the rates of maternal mortality continue to increase and issues surrounding maternal mortality are not addressed or resolved.

In light of the above, there is a wide gap that needs to be filled by different stake holders to fight this vice and reduce maternal mortality in Uganda so as to achieve social justice in health.

Namaganda Jane Kibira and Ajalo Ruth

Center for Health Human Rights and Development. (CEHURD)